Yesterday I went to a briefing at the COP21 summit on how realistic achieving a 1.5 degree target as part of the Paris climate deal is, as opposed to the 2 degree target that was first proposed. At the end of the briefing, I spoke to the climate scientist who had been outlining the case that 1.5 degrees is achievable, and handed him a copy of our new report, which questions all of the underlying assumptions of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS).

He looked at me and said: “You do realise that 1.5 degrees won’t work without BECCS, right?”.

To which I replied: “Yes, but BECCS won’t work either.”

“Without BECCS, it’s impossible.” he replied again.

Here was a well respected, well published, and socially-concious climate scientist, participating in an NGO briefing, and advocating the roll-out of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage at an unprecedented scale. Though he didn’t actually say so. This short but bizarre conversation neatly highlights the crux of the problem with any emissions reductions targets that will come out of Paris. Achieving them will be based on a phantom technology, that can’t be scaled up, and is as likely to save the planet from climate chaos as the miraculous arrival to Earth of carbon-sequestering extra terrestrials.

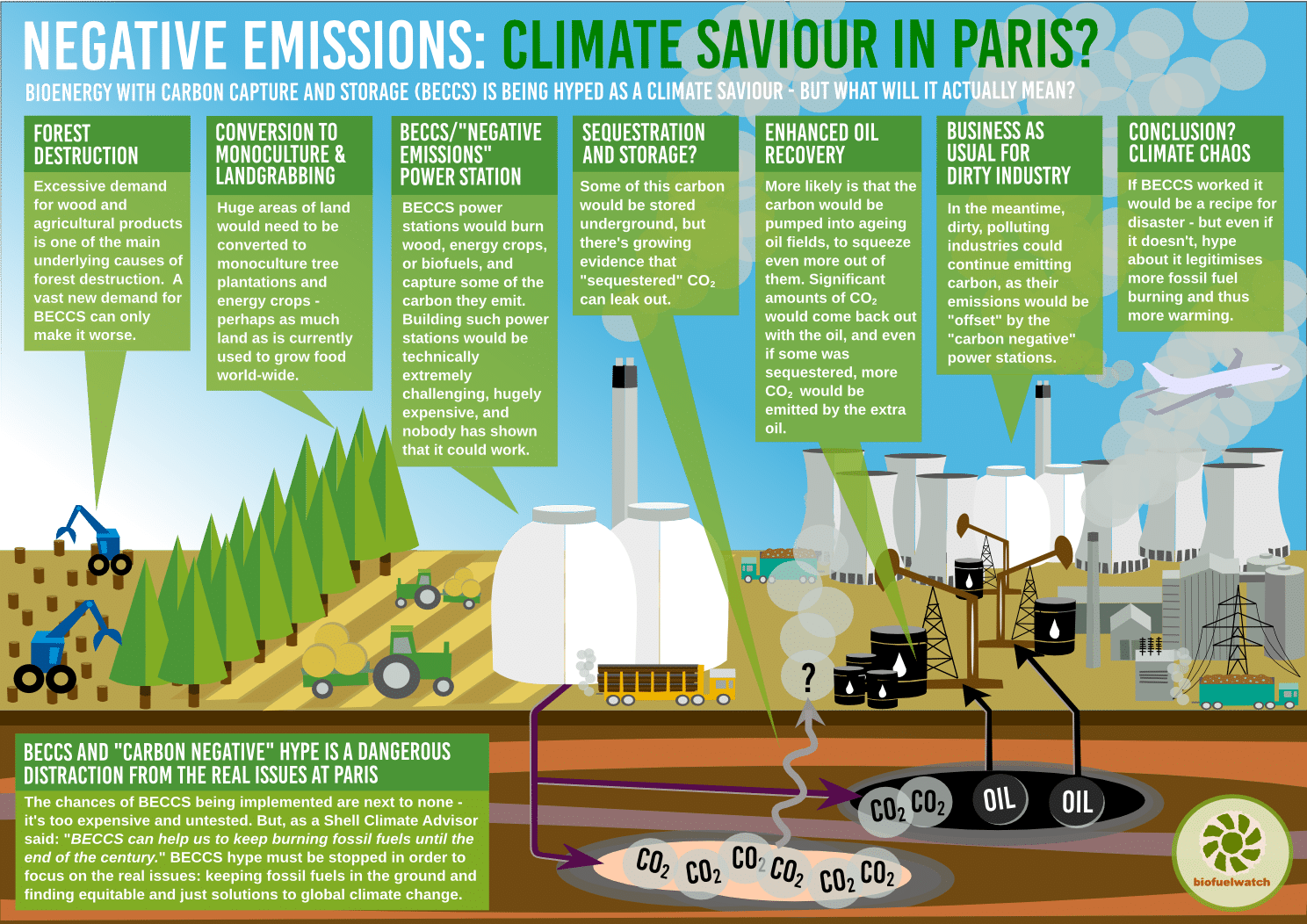

Most of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) scenarios that limit global temperature increases to 2 degrees include some form of “negative emissions”. That’s the idea that carbon can be sucked out of the atmosphere and stored in a solid form, not in the atmosphere. Exactly like a tree does. But according to the IPCC, the most appropriate technology that will be capable of doing this is BECCS, where carbon is captured from bioenergy infrastructure like biomass power stations or biofuel refineries, and pumped underground.

This is really significant – it means that the IPCC and most of its models don’t think that limiting global temperature rises to 2 degrees is possible through emissions reductions alone (achieved through, say, leaving fossil fuels in the ground and halting deforestation) without a technology that, for all intents and proposes, doesn’t exist yet. And it’s for this reason that the Paris climate agreement will use the language of “net emissions reductions”, instead of simply “emissions reductions”.

The 1.5, 2 or 3 degrees debate is a purely a semantic one if underlying all of these targets is the belief by governments and industry that they can keep on polluting, because negative emissions technologies will allow this pollution to be offset. It’s also semantic because nobody knows for sure how sensitive the climate actually is to greenhouse gases. The only possibility of avoiding 1.5 degrees warming would be for climate sensitivity to be at the lowest end of what models suggests. Which is hardly something that can be negotiated in Paris.

Dangerously high CO2 levels in the atmosphere do require us to work towards meaningful and applicable responses. And these do exist – keeping fossil fuels in the ground, ending the destruction of ecosystems and soils, and tackling emissions from agriculture are real and proven ways of ending greenhouse gas emissions. And we do need to find proven ways of removing past emissions from the atmosphere. Replacing industrial agriculture with agroecology, and allowing degraded and destroyed ecosystems to regenerate or helping to restore them, are proven ways of doing so. But proposing sci-fi “solutions” like BECCS to the climate crisis is totally irresponsible.

Biofuelwatch has just published the first critical and in-depth study on BECCS. The report examines the different BECCS technologies proposed, and the role of the IPCC in this debate. So far, only very small-scale BECCS projects have been attempted, and have all involved capturing some CO2 from ethanol refining. However, the carbon emissions from the fossil fuels burned to power the refineries are greater than the amount of carbon captured, and not even the companies involved say that these projects are carbon-negative. In relation to carbon capture from power plants, the report also carefully examines the experience with coal-fired Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) projects. It looks in detail at the technical and economic viability of the technologies involved, at the credibility of the idea that large-scale BECCS could be carbon-negative, at the evidence regarding the reliability of carbon storage, and at the greenhouse gas impacts of combining Carbon Capture and Storage with Enhanced Oil Recovery.

The report can be downloaded here, and for more on the BECCS issue in the context of the Paris climate talks, please read this article by Biofuelwatch co-Director Almuth Ernsting.